Last week, The Open Source Initiative (OSI) released the first version of its Open Source AI Definition (OSAID), which aims to become a standard by which one can evaluate whether an AI system is open-source. Briefly put, an AI system is considered open-source under the OSAID if there is enough information available on it such that users can apply the system to any purpose without needing to ask for permission, they can gain a substantial understanding of how the system works—for instance, enough to be able to modify its components, and they can share the system, regardless of whether it has undergone modifications or the purpose it's supposed to fulfill.

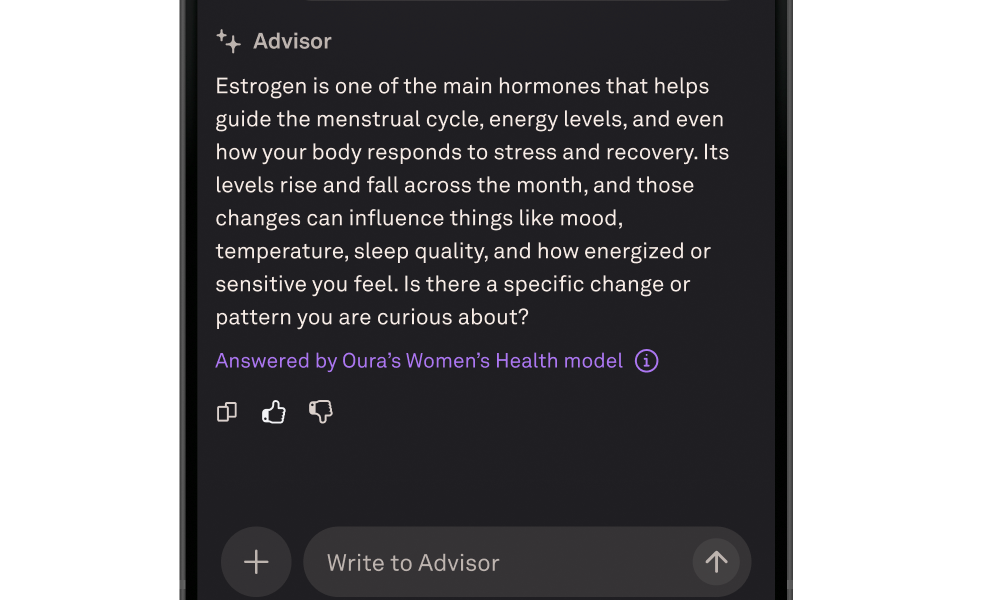

Expectedly, the OSAID doesn't apply to many systems in the market that have been promoted as open-source at certain points in their existence. The most prominent of these systems is undoubtedly Meta's Llama model family. These models were originally introduced as the "best free and open-source" models in the market. While Meta no longer uses the term "open-source" to market these products, it still calls them "open" or "open weights" as if to emphasize a crucial difference with other closed-source models.

Notably, the company withdrew its participation from a panel that took place last Wednesday at TechCrunch Disrupt 2024, where Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence CEO Ali Farhadi and Hugging Face Head of Global Policy Irene Solaiman discussed several topics related to how open-source AI may change the face of the industry. Farhadi largely agreed with the definition as a step in the right direction, while remarking on the need to refine certain details and less common scenarios, such as what would happen if someone used a proprietary model to generate data, and then pack the data within an open-source AI system.

The panelists also acknowledged a common misconception that "closed" (as in a closed-source model) is synonymous with "safe." Allegedly, something similar cannot be said about open-source AI systems. The discussion also touched on the distinction between accessibility, and open source. By conflating many of these terms, and not considering other aggravating factors—Solaiman remarked how she has more reservations about AI-powered voice cloning than other modalities, regardless of whether they are closed or not— we risk miscalculating the potential for misuse corresponding to individual systems and falling into the ideology that open source is inherently unsafe.

To close the discussion, the panelists shared their views on the current status of regulations and their expectations for the future. Among several topics, they highlighted the difficulties associated with navigating regulation and policy creation that requires answering hard questions such as whether open-source AI systems should be treated differently than closed-source ones, or whether we should look at the individual contributions of those in charge of different components when looking for accountability or assigning responsibilities. Regardless, the session ended with an optimistic outlook for open-source AI systems.

Comments